The technological and industrial history of the United States describes the United States' emergence as one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world. The availability of land and literate labor, the absence of a landed aristocracy, the prestige of entrepreneurship, the diversity of climate and large easily accessed upscale and literate markets all contributed to America's rapid

industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

. The availability of capital, development by the free market of navigable rivers and coastal waterways, as well as the abundance of natural resources facilitated the cheap extraction of energy all contributed to America's rapid industrialization. Fast transport by the very large railroad built in the mid-19th century, and the

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. Th ...

built in the late 20th century, enlarged the markets and reduced shipping and production costs. The legal system facilitated business operations and guaranteed contracts. Cut off from Europe by the embargo and the British blockade in the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

(1807–15), entrepreneurs opened factories in the Northeast that set the stage for rapid industrialization modeled on British innovations.

From its emergence as an independent nation, the United States has encouraged science and innovation. As a result, the United States has been the birthplace of 161 of Britannica's 321 Greatest Inventions, including items such as the

airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spe ...

,

internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

,

microchip

An integrated circuit or monolithic integrated circuit (also referred to as an IC, a chip, or a microchip) is a set of electronic circuits on one small flat piece (or "chip") of semiconductor material, usually silicon. Large numbers of tiny ...

,

laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word "laser" is an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". The fir ...

,

cellphone

A mobile phone, cellular phone, cell phone, cellphone, handphone, hand phone or pocket phone, sometimes shortened to simply mobile, cell, or just phone, is a portable telephone that can make and receive calls over a radio frequency link whil ...

,

refrigerator,

email

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic ( digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" meant ...

,

microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency ran ...

,

personal computer

A personal computer (PC) is a multi-purpose microcomputer whose size, capabilities, and price make it feasible for individual use. Personal computers are intended to be operated directly by an end user, rather than by a computer expert or tec ...

,

liquid-crystal display

A liquid-crystal display (LCD) is a flat-panel display

A flat-panel display (FPD) is an electronic display used to display visual content such as text or images. It is present in consumer, medical, transportation, and industrial equipmen ...

and

light-emitting diode

A light-emitting diode (LED) is a semiconductor device that emits light when current flows through it. Electrons in the semiconductor recombine with electron holes, releasing energy in the form of photons. The color of the light (cor ...

technology,

air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C or AC, is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior environment (sometimes referred to as 'comfort cooling') and in some cases also strictly controlling ...

,

assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in seq ...

,

supermarket

A supermarket is a self-service Retail#Types of outlets, shop offering a wide variety of food, Drink, beverages and Household goods, household products, organized into sections. This kind of store is larger and has a wider selection than earli ...

,

bar code

A barcode or bar code is a method of representing data in a visual, machine-readable form. Initially, barcodes represented data by varying the widths, spacings and sizes of parallel lines. These barcodes, now commonly referred to as linear or o ...

, and

automated teller machine

An automated teller machine (ATM) or cash machine (in British English) is an electronic telecommunications device that enables customers of financial institutions to perform financial transactions, such as cash withdrawals, deposits, fun ...

.

The early technological and industrial development in the United States was facilitated by a unique confluence of geographical, social, and economic factors. The relative lack of workers kept the United States wages generally higher than corresponding British and European workers and provided an incentive to mechanize some tasks. The United States population had some semi-unique advantages in that they were former

British subjects, had high English literacy skills, for that period (over 80% in New England), had strong British institutions, with some minor American modifications, of courts, laws, right to vote, protection of property rights and in many cases personal contacts among the British innovators of the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. They had a good basic structure to build on. Another major advantage, which the British lacked, was no inherited aristocratic institutions. The

eastern seaboard of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

, with a great number of rivers and streams along the Atlantic seaboard, provided many potential sites for constructing textile mills necessary for early industrialization. The technology and information on how to build a textile industry were largely provided by

Samuel Slater

Samuel Slater (June 9, 1768 – April 21, 1835) was an early English-American industrialist known as the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution" (a phrase coined by Andrew Jackson) and the "Father of the American Factory System". In the ...

(1768–1835) who emigrated to New England in 1789. He had studied and worked in British textile mills for a number of years and immigrated to the United States, despite restrictions against it, to try his luck with U.S. manufacturers who were trying to set up a textile industry. He was offered a full partnership if he could succeed—he did. A vast supply of natural resources, the technological knowledge on how to build and power the necessary machines along with a labor supply of mobile workers, often unmarried females, all aided early industrialization. The broad knowledge carried by European migrants of two periods that advanced the societies there, namely the European Industrial Revolution and European

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

, helped facilitate understanding for the construction and invention of new manufacturing businesses and technologies. A limited government that would allow them to succeed or fail on their own merit helped.

After the close of the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

in 1783, the new government continued the strong property rights established under British rule and established a rule of law necessary to protect those property rights. The idea of issuing

patents

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

was incorporated into Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution authorizing Congress "to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries." The invention of the

Cotton Gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

by American

Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

made cotton potentially a cheap and readily available resource in the United States for use in the new textile industry.

One of the real impetuses for the United States entering the Industrial Revolution was the passage of the

Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

, the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

(1812–14) and the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1803–15) which cut off supplies of new and cheaper Industrial revolution products from Britain. The lack of access to these goods all provided a strong incentive to learn how to develop the industries and to make their own goods instead of simply buying the goods produced by Britain.

Modern productivity researchers have shown that the period in which the greatest economic and technological progress occurred was between the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. During this period the nation was transformed from an agricultural economy to the foremost industrial power in the world, with more than a third of the global industrial output. This can be illustrated by the index of total industrial production, which increased from 4.29 in 1790 to 1,975.00 in 1913, an increase of 460 times (base year 1850 – 100).

American colonies

gained independence in 1783 just as profound changes in industrial production and coordination were beginning to

shift production from artisans to factories. Growth of the nation's transportation infrastructure with

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

and a confluence of technological innovations before the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

facilitated an expansion in organization, coordination, and

scale of industrial production. Around the turn of the 20th century, American industry had superseded its European counterparts economically and the nation began to assert its

military power. Although the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

challenged its

technological momentum, America emerged from it and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

as one of two global

superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural s ...

s. In the second half of the 20th century, as the United States was drawn into competition with the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

for

political, economic, and military primacy, the government invested heavily in scientific research and technological development which spawned advances in

spaceflight

Spaceflight (or space flight) is an application of astronautics to fly spacecraft into or through outer space, either with or without humans on board. Most spaceflight is uncrewed and conducted mainly with spacecraft such as satellites in or ...

,

computing

Computing is any goal-oriented activity requiring, benefiting from, or creating computing machinery. It includes the study and experimentation of algorithmic processes, and development of both hardware and software. Computing has scientific, e ...

, and

biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

.

Science, technology, and industry have not only profoundly shaped America's economic success, but have also contributed to its distinct political institutions, social structure, educational system, and cultural identity.

Pre-European technology

North America has been inhabited continuously since approximately 4,000 BC. The earliest inhabitants were

nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

ic, big-game

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s who crossed the

Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of ...

. These first

Native Americans relied upon chipped-stone

spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

heads, rudimentary

harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, seal hunting, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the t ...

s, and boats clad in animal hides for hunting in the

Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

. As they dispersed within the continent, they encountered the varied temperate climates in the Pacific northwest, central plains, Appalachian woodlands, and arid Southwest, where they began to make permanent settlements. The peoples living in the Pacific northwest built wooden houses, used

nets and

weirs

A weir or low head dam is a barrier across the width of a river that alters the flow characteristics of water and usually results in a change in the height of the river level. Weirs are also used to control the flow of water for outlets of l ...

to catch fish, and practiced

food preservation

Food preservation includes processes that make food more resistant to microorganism growth and slow the oxidation of fats. This slows down the decomposition and rancidification process. Food preservation may also include processes that inhibit ...

to ensure longevity of their food sources, since substantial agriculture was not developed. Peoples living on the plains remained largely nomadic (some practiced agriculture for parts of the year) and became adept

leather workers as they hunted

buffalo while people living in the arid southwest built

adobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for ''mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of e ...

buildings, fired

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

, domesticated

cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

, and

wove cloth. Tribes in the

eastern woodlands

The Eastern Woodlands is a cultural area of the indigenous people of North America. The Eastern Woodlands extended roughly from the Atlantic Ocean to the eastern Great Plains, and from the Great Lakes region to the Gulf of Mexico, which is now p ...

and

Mississippian Valley developed extensive trade networks, built

pyramid-like mounds, and practiced substantial agriculture while the peoples living in the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

and coastal Atlantic practiced highly sustainable forest agriculture and were expert woodworkers. However, the populations of these peoples were small and their rate of technological change was very low. Indigenous peoples did not

domesticate

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. A ...

animals for

drafting or

husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, selective breeding, and the raising of livestock. Husbandry has a long history, starti ...

, develop writing systems, or create

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

or

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

-based tools like their European/Asian counterparts.

Colonial era

Agriculture

In the 17th century,

Pilgrims,

Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

, and

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

fleeing religious persecution in Europe brought with them

plowshare

In agriculture, a plowshare ( US) or ploughshare ( UK; ) is a component of a plow (or plough). It is the cutting or leading edge of a moldboard which closely follows the coulter (one or more ground-breaking spikes) when plowing.

The plowshar ...

s,

gun

A gun is a ranged weapon designed to use a shooting tube (gun barrel) to launch projectiles. The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid (e.g. in water guns/cannons, spray guns for painting or pressure washing, p ...

s, and domesticated animals like

cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

s and

pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s. These immigrants and other European colonists initially farmed subsistence crops like

corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

,

wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

,

rye, and

oats

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human con ...

as well as rendering

potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form. and

maple syrup

Maple syrup is a syrup made from the sap of maple trees. In cold climates, these trees store starch in their trunks and roots before winter; the starch is then converted to sugar that rises in the sap in late winter and early spring. Maple tree ...

for trade. Due to the more temperate climate, large-scale

plantations in the American South

A plantation complex in the Southern United States is the built environment (or complex) that was common on agricultural plantations in the American South from the 17th into the 20th century. The complex included everything from the main resid ...

grew labor-intensive cash crops like

sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

,

rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

,

cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

, and

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

requiring native and imported African slave labor to maintain. Early American farmers were not self-sufficient; they relied upon other farmers, specialized craftsmen, and merchants to provide tools, process their harvests, and bring them to market.

Artisanship

Colonial artisanship emerged slowly as the market for advanced craftsmanship was small. American artisans developed a more relaxed (less regulated) version of the Old World apprenticeship system for educating and employing the next generation. Despite the fact that

mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce ...

, export-heavy economy impaired the emergence of a robust self-sustaining economy, craftsmen and merchants developed a growing interdependence on each other for their trades. In the mid-18th century, attempts by the British to subdue or control the colonies by means of taxation sowed increased discontent among these artisans, who increasingly joined the

Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

cause.

Silver working

Colonial Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

provided a potential market of rich

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

. At least 19 silversmiths worked in

Williamsburg between 1699 and 1775. The best-known were James Eddy (1731–1809) and his brother-in-law William Wadill, also an engraver. Most planters, however, purchased English-made silver.

In

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

,

goldsmiths

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold.

In German, the Goldsmith family name is written Goldschmidt.

Goldsmith may also refer to:

Places

* Goldsmith, Indiana, United States

* Goldsmith, New York, United States, a h ...

and

silversmiths

A silversmith is a metalworker who crafts objects from silver. The terms ''silversmith'' and ''goldsmith'' are not exactly synonyms as the techniques, training, history, and guilds are or were largely the same but the end product may vary great ...

were stratified. The most prosperous were merchant-artisans, with a business outlook and high status. Most craftsmen were laboring artisans who either operated small shops or, more often, did piecework for the merchant artisans. The small market meant there was no steady or well-paid employment; many lived in constant debt.

Colonial silver working was pre-industrial in many ways: many pieces made were "bespoke," or uniquely made for each customer, and emphasized artistry as well as functionality. Silver (and other metal) mines were scarcer in North America than in Europe, and colonial craftsmen had no consistent source of materials with which to work. For each piece of silver they crafted, raw materials had to be collected and often reused from disparate sources, most commonly

Spanish coins. The purity of these sources was not regulated, nor was there an organized

supply chain

In commerce, a supply chain is a network of facilities that procure raw materials, transform them into intermediate goods and then final products to customers through a distribution system. It refers to the network of organizations, people, acti ...

through which to obtain silver. As silver objects were sold by weight, manufacturers who could produce silver objects cheaply by mass had an advantage. Many of these unique, individual aspects to silver working kept artisan practices in place through the late 18th century.

As demand for silver increased and large-scale manufacturing techniques emerged, silver products became much more standardized. For special-order objects that would likely only be made once, silversmiths generally used

lost-wax casting

Lost-wax casting (also called "investment casting", "precision casting", or ''cire perdue'' which has been adopted into English from the French, ) is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass, or bronze) i ...

, in which a sculpted object was carved out of wax, an

investment casting

Investment casting is an industrial process based on lost-wax casting, one of the oldest known metal-forming techniques. The term "lost-wax casting" can also refer to modern investment casting processes.

Investment casting has been used in var ...

was made, and the wax was melted away. The molds produced in this manner could only be used once, which made them inconvenient for standard objects like handles and buckles.

Permanent mold casting

Permanent mold casting is a metal casting process that employs reusable molds ("permanent molds"), usually made from metal. The most common process uses gravity to fill the mold, however gas pressure or a vacuum are also used. A variation on the ...

, an industrial casting technique focused on high-volume production, allowed smiths to reuse molds to make exact replicas of the most commonly used items they sold. In creating these molds and developing standardized manufacturing processes, silversmiths could begin delegating some work to

apprentices

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

and

journeymen

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

. For instance, after 1780,

Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

's sons took on more significant roles in his shop, and his silver pieces often included wooden handles made by carpenters more experienced with woodwork. For even some of the most successful artisans like Revere, artisan was not a profitable enterprise compared to mass-production using iron or bronze casting. Creating products that could be replicated for multiple customers, adopting new business practices and labor policies, and new equipment made manufacturing more ultimately efficient. These changes, in tandem with new techniques and requirements defined by changing social standards, led to the introduction of new manufacturing techniques in Colonial America that preceded and anticipated the industrial revolution.

Late in the colonial era a few silversmiths expanded operations with manufacturing techniques and changing business practices They hired assistants, subcontracted out piecework and standardized output. One individual in the vanguard of America's shift towards more industrial methods was

Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

, who emphasized the production of increasingly standardized items later in his career with the use of a silver flatting mill, increased numbers of salaried employees, and other advances. Still, traditional methods of artisan remained, and smiths performed a great deal of work by hand. The coexistence of the craft and industrial production styles prior to the industrial revolution is an example of

proto-industrialization

Proto-industrialization is the regional development, alongside commercial agriculture, of rural handicraft production for external markets.

The term was introduced in the early 1970s by economic historians who argued that such developments in par ...

.

Factories and mills

In the mid-1780s,

Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advoca ...

invented an automated flour mill that included a

grain elevator

A grain elevator is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lower level and deposits ...

and

hopper boy

Hopper or hoppers may refer to:

Places

*Hopper, Illinois

* Hopper, West Virginia

* Hopper, a mountain and valley in the Hunza–Nagar District of Pakistan

* Hopper (crater), a crater on Mercury

People with the name

* Hopper (surname)

* Grace Ho ...

. Evans' design eventually displaced the traditional

gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and Wheat middlings, middlings. The term can refer to either the Mill (grinding), grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist i ...

s. By the turn of the century, Evans also developed one of the first high-pressure

steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

s and began establishing a network of machine workshops to manufacture and repair these popular inventions. In 1789, the widow of

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependabl ...

recruited

Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

to develop a machine to separate the seeds of short fibered cotton from the fibers. The resulting

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

could be made with basic carpentry skills but reduced the necessary labor by a factor of 50 and generated huge profits for cotton growers in the South. While Whitney did not realize financial success from his invention, he moved on to manufacturing rifles and other armaments under a government contract that could be made with "expedition, uniformity, and exactness"—the foundational ideas for

interchangeable parts

Interchangeable parts are parts ( components) that are identical for practical purposes. They are made to specifications that ensure that they are so nearly identical that they will fit into any assembly of the same type. One such part can freely r ...

. However, Whitney's vision of

interchangeable parts

Interchangeable parts are parts ( components) that are identical for practical purposes. They are made to specifications that ensure that they are so nearly identical that they will fit into any assembly of the same type. One such part can freely r ...

would not be achieved for over two decades with firearms and even longer for other devices.

Between 1800 and 1820, new industrial tools that rapidly increased the quality and efficiency of manufacturing emerged.

Simeon North

Simeon North (July 13, 1765 – August 25, 1852) was a Middletown, Connecticut, gun manufacturer, who developed one of America's first milling machines (possibly the very first) in 1818 and played an important role in the development of interchan ...

suggested using

division of labor

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, and ...

to increase the speed with which a complete

pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, an ...

could be manufactured which led to the development of a

milling machine

Milling is the process of machining using rotary cutters to remove material by advancing a cutter into a workpiece. This may be done by varying direction on one or several axes, cutter head speed, and pressure. Milling covers a wide variety of d ...

in 1798. In 1819,

Thomas Blanchard created a

lathe

A lathe () is a machine tool that rotates a workpiece about an axis of rotation to perform various operations such as cutting, sanding, knurling, drilling, deformation, facing, and turning, with tools that are applied to the workpiece to c ...

that could reliably cut irregular shapes, like those needed for arms manufacture. By 1822,

Captain John H. Hall

John Hancock Hall (January 4, 1781 – February 26, 1841) was the inventor of the M1819 Hall breech-loading rifle and a mass production innovator.

Early life

Hall was born in 1781 in Portland, Maine. He worked in his father's tannery until setti ...

had developed a system using

machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, boring, grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some sort of tool that does the cutting or shaping. All m ...

s, division of labor, and an unskilled workforce to produce a

breech-loading rifle

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally bre ...

—a process that came to be known as "

Armory practice" in the U.S. and the ''

American system of manufacturing

The American system of manufacturing was a set of manufacturing methods that evolved in the 19th century. The two notable features were the extensive use of interchangeable parts and mechanization for production, which resulted in more efficient us ...

'' in England.

The

textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of yarn, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

Industry process

Cotton manufacturi ...

, which had previously relied upon labor-intensive production methods, was also rife with potential for mechanization. In the late 18th century, the English textile industry had adopted the

spinning jenny

The spinning jenny is a multi-spindle spinning frame, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of textile manufacturing during the early Industrial Revolution. It was invented in 1764 or 1765 by James Hargreaves in Stanhill ...

,

water frame

The water frame is a spinning frame that is powered by a water-wheel. Water frames in general have existed since Ancient Egypt times. Richard Arkwright, who patented the technology in 1769, designed a model for the production of cotton thread; ...

, and

spinning mule

The spinning mule is a machine used to spin cotton and other fibres. They were used extensively from the late 18th to the early 20th century in the mills of Lancashire and elsewhere. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of tw ...

which greatly improved the efficiency and quality of textile manufacture, but were closely guarded by the British government which forbade their export or the emigration of those who were familiar with the technology. The 1787

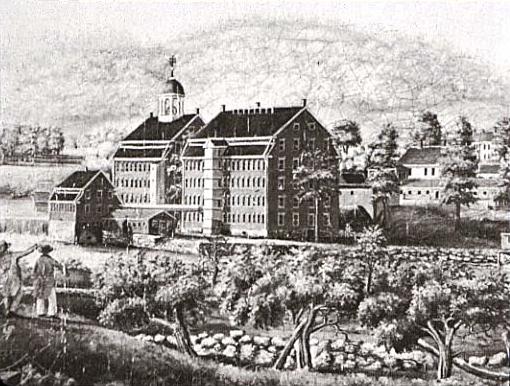

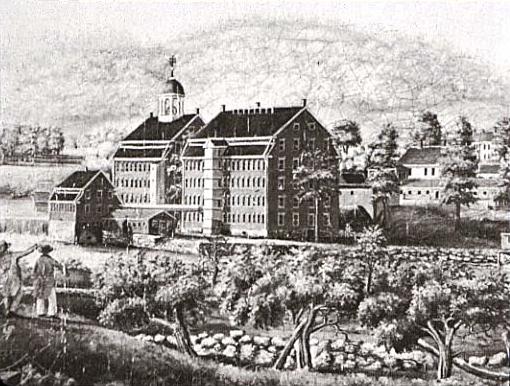

Beverly Cotton Manufactory

Beverly Cotton Manufactory was the first cotton mill built in America, and the largest cotton mill to be built during its era. It was built hoping for economic success, but reached a downturn due to technical limitations of the then early produ ...

was the first

cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning (textiles), spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Althou ...

in the United States, but it relied on horse power.

Samuel Slater

Samuel Slater (June 9, 1768 – April 21, 1835) was an early English-American industrialist known as the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution" (a phrase coined by Andrew Jackson) and the "Father of the American Factory System". In the ...

, an apprentice in one of the largest textile factories in England, immigrated to the United States in 1789 upon learning that American states were paying bounties to British expatriates with a knowledge of textile machinery. With the help of

Moses Brown of Providence, Slater established America's oldest currently existing cotton-spinning mill with a fully mechanized water power system at the

Slater Mill

The Slater Mill is a historic water-powered textile mill complex on the banks of the Blackstone River in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, modeled after cotton spinning mills first established in England. It is the first water-powered cotton spinning mil ...

in

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Pawtucket is a city in Providence County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 75,604 at the 2020 census, making the city the fourth-largest in the state. Pawtucket borders Providence and East Providence to the south, Central Falls ...

in 1793.

Hoping to harness the ample power of the

Merrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into Mas ...

, another group of investors began building the

Middlesex Canal

The Middlesex Canal was a 27-mile (44-kilometer) barge canal connecting the Merrimack River with the port of Boston. When operational it was 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and 3 feet (0.9 m) deep, with 20 locks, each 80 feet (24 m) long and between 10 and ...

up the

Mystic River

The Mystic River is a riverU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 in Massachusetts, in the United States. In Massachusett, means "large estuary," alluding to t ...

, both Mystic Lakes and generally following

stream valleys (near to today's

MA 38) reached the Merrimack in

Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It is located north-east of London a ...

from

Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

Since ...

, establishing limited operations by 1808, and a system of

navigations

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flo ...

and canals reaching past

Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

by mid-1814—and spawning commercial activities, and especially new clothing mills throughout the region. At nearly the same time as the canal was completed,

Francis Cabot Lowell

Francis Cabot Lowell (April 7, 1775 – August 10, 1817) was an American businessman for whom the city of Lowell, Massachusetts, is named. He was instrumental in bringing the Industrial Revolution to the United States.

Early life

Francis Cabot ...

and a consortium of businessmen set up the clothing mills in

Waltham, Massachusetts

Waltham ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, and was an early center for the labor movement as well as a major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. The original home of the Boston Manufacturing Company, th ...

making use of water power from the

Charles River

The Charles River ( Massachusett: ''Quinobequin)'' (sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles) is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton to Boston along a highly meandering route, that doubles b ...

with the concept of housing together production of feedstocks complete consumer processes so raw materials entered, and dyed fabrics or clothing left. For a few decades, it seemed that every

lock

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

along the canal had mills and water wheels. In 1821,

Boston Manufacturing Company

The Boston Manufacturing Company was a business that operated one of the first factories in America. It was organized in 1813 by Francis Cabot Lowell, a wealthy Boston merchant, in partnership with a group of investors later known as The Boston A ...

built a major expansion in East Chelmsford, which was soon incorporated as

Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020, it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as of ...

—which came to dominate the cloth production and clothing industry for decades.

Slater's Mill was established in the

Blackstone Valley

The Blackstone Valley or Blackstone River Valley is a region of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. It was a major factor in the American Industrial Revolution. It makes up part of the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor and Nation ...

, which extended into neighboring

, (

Daniel Day's Woolen Mill, 1809 at

Uxbridge

Uxbridge () is a suburban town in west London and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Situated west-northwest of Charing Cross, it is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the London Plan. Uxbrid ...

), and became one of the earliest industrialized region in the United States, second to the

North Shore of Massachusetts. Slater's business model of independent mills and mill villages (the "

Rhode Island System") began to be replaced by the 1820s by a more efficient system (the "

Waltham System

The Waltham-Lowell system was a labor and production model employed during the rise of the textile industry in the United States, particularly in New England, amid the larger backdrop of rapid expansion of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1 ...

") based upon

Francis Cabot Lowell

Francis Cabot Lowell (April 7, 1775 – August 10, 1817) was an American businessman for whom the city of Lowell, Massachusetts, is named. He was instrumental in bringing the Industrial Revolution to the United States.

Early life

Francis Cabot ...

's replications of British

power looms

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed in 1786 by Edmund Cartwright and first built that same year. ...

. Slater went on to build several more cotton and wool mills throughout

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, but when faced with a labor shortage, resorted to building housing, shops, and churches for the workers and their families adjacent to his factories. The first

power looms

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed in 1786 by Edmund Cartwright and first built that same year. ...

for woolens were installed in 1820, at

Uxbridge, Massachusetts

Uxbridge is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts first colonized in 1662 and incorporated in 1727. It was originally part of the town of Mendon, MA, Mendon, and named for the Marquess of Anglesey, Earl of Uxbridge. The town is located south ...

, by

John Capron

John Willard Capron (February 14, 1797, at Uxbridge, Worcester County, Massachusetts – December 25, 1878, at Uxbridge) was an American military officer in the infantry, state legislator, and textile manufacturer. Famous for being a military unif ...

, of

Cumberland, Rhode Island. These added automated weaving under the same roof, a step which Slater's system outsourced to local farms. Lowell looms were managed by specialized employees, many of the employed were unmarried young women ("

Lowell mill girls"), and owned by a corporation. Unlike the previous forms of labor (

apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a Tradesman, trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners ...

, family labor,

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and

indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

), the Lowell system popularized the concept of

wage laborer who sells his labor to an employer under contract—a socio-economic system which persists in many modern countries and industries. The corporation also looked out for the health and well-being of the young women, including their spiritual health, and the hundreds of women employed by it culturally established the pattern of a young woman going off to work for a few years to save money before returning home to school and marriage. It created an independent breed of women uncommon in most of the world.

Turnpikes and canals

Even as the country grew even larger with the admission of

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

,

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, and

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

by 1803, the only means of transportation between these landlocked western states and their coastal neighbors was by foot, pack animal, or ship. Recognizing the success of

Roman road

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

s in unifying that empire, political and business leaders in the United States began to construct roads and canals to connect the disparate parts of the nation.

Early

toll road

A toll road, also known as a turnpike or tollway, is a public or private road (almost always a controlled-access highway in the present day) for which a fee (or ''toll'') is assessed for passage. It is a form of road pricing typically implemented ...

s were constructed and owned by

joint-stock companies

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders are ...

that sold stock to raise construction capital like

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

's 1795

Lancaster Turnpike Company. In 1808,

Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan– American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

's ''Report on the Subject of Public Roads and Canals'' suggested that the federal government should fund the construction of interstate

turnpikes and

canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

s. While many

Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

opposed the federal government assuming such a role, the British blockade in the War of 1812 demonstrated the United States' reliance upon these overland roads for military operations as well as for general commerce. Construction on the

National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the Federal Government of the United States, federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Pot ...

began in 1815 in

Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Allegany County, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its s ...

and reached

Wheeling, Virginia in 1818, but political strife thereafter ultimately prevented its western advance to the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Nevertheless, the road became a primary overland conduit through

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

and was the gateway for thousands of antebellum westward-bound settlers.

Numerous canal companies had also been chartered; but of all the canals projected, only three had been completed when the War of 1812 began: the

Dismal Swamp Canal

The Dismal Swamp Canal is a canal located along the eastern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina in the United States. Opened in 1805, it is the oldest continually operating man-made canal in the United States. It is par ...

in Virginia, the

Santee Canal

The Santee Canal was one of the earliest canals built in the United States. It was built to provide a direct water route between Charleston and Columbia, the new South Carolina state capital. It was named to the National Register of Historic Plac ...

in South Carolina, and the

Middlesex Canal

The Middlesex Canal was a 27-mile (44-kilometer) barge canal connecting the Merrimack River with the port of Boston. When operational it was 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and 3 feet (0.9 m) deep, with 20 locks, each 80 feet (24 m) long and between 10 and ...

in Massachusetts. It remained for New York to usher in a new era in internal communication by authorizing in 1817 the construction of the

Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

. This bold bid for Western trade alarmed the merchants of Philadelphia, particularly as the completion of the national road threatened to divert much of their traffic to Baltimore. In 1825, the

Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

grappled with the problem by projecting a series of canals which were to connect its great seaport with Pittsburgh on the west and with

Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

and the upper

Susquehanna on the north. The

Blackstone Canal, (1823–1828) in

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

and

, and the

Morris Canal

The Morris Canal (1829–1924) was a common carrier anthracite coal canal across northern New Jersey that connected the two industrial canals at Easton, Pennsylvania across the Delaware River from its western terminus at Phillipsburg, New Jers ...

across northern

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

(1824–1924) soon followed, along with the

Illinois and Michigan Canal

The Illinois and Michigan Canal connected the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. In Illinois, it ran from the Chicago River in Bridgeport, Chicago to the Illinois River at LaSalle-Peru. The canal crossed the Chicago Por ...

from

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

to the

Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the D ...

(1824–1848).

Like the turnpikes, the early canals were constructed, owned, and operated by private joint-stock companies but later gave way to larger projects funded by the states. The

Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, proposed by

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

De Witt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and naturalist. He served as a United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the seventh governor of New York. In this last capacity, he was largely resp ...

, was the first canal project undertaken as a public good to be financed at the public risk through the issuance of

bonds. When the project was completed in 1825, the canal linked

Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

with the

Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

through 83 separate locks and over a distance of . The success of the Erie Canal spawned a boom of other canal-building around the country: over of artificial waterways were constructed between 1816 and 1840. Small towns like

Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffa ...

,

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

, and

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

that lay along major canal routes boomed into major industrial and trade centers, while canal-building pushed some states like

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

,

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, and

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

to the brink of

bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor ...

.

The magnitude of the transportation problem was such, however, that neither individual states nor private corporations seemed able to meet the demands of an expanding internal trade. As early as 1807,

Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan– American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

had advocated the construction of a great system of internal waterways to connect East and West, at an estimated cost of $20,000,000 ($ in consumer dollars). But the only contribution of the national government to

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

during the Jeffersonian era was an appropriation in 1806 of two percent of the net proceeds of the sales of public lands in Ohio for the construction of a national road, with the consent of the states through which it should pass. By 1818 the road was open to traffic from

Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Allegany County, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its s ...

, to

Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in the U.S. state of West Virginia. Located almost entirely in Ohio County, of which it is the county seat, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and also contains a tiny portion extending ...

.

In 1816, with the experiences of the war before him, no well-informed statesman could shut his eyes to the national aspects of the problem. Even President

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

invited the attention of Congress to the need of establishing "a comprehensive system of roads and canals". Soon after Congress met, it took under consideration a bill drafted by

John C. Calhoun which proposed an appropriation of $1,500,000 ($ in consumer dollars) for internal improvements. Because this appropriation was to be met by the moneys paid by the National Bank to the government, the bill was commonly referred to as the "Bonus Bill". But on the day before he left office, President Madison vetoed the bill because it was unconstitutional. The policy of internal improvements by federal aid was thus wrecked on the constitutional scruples of the last of the

Virginia dynasty. Having less regard for consistency, the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

recorded its conviction, by close votes, that Congress could appropriate money to construct roads and canals, but had not the power to construct them. As yet the only direct aid of the national government to internal improvements consisted of various appropriations, amounting to about $1,500,000 for the

Cumberland Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

.

As the country recovered from financial depression following the

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

, the question of internal improvements again forged to the front. In 1822, a bill to authorize the collection of tolls on the Cumberland Road had been vetoed by President

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. In an elaborate essay, Monroe set forth his views on the constitutional aspects of a policy of internal improvements. Congress might appropriate money, he admitted, but it might not undertake the actual construction of national works nor assume jurisdiction over them. For the moment, the drift toward a larger participation of the national government in internal improvements was stayed. Two years later, Congress authorized the President to institute surveys for such roads and canals as he believed to be needed for commerce and military defense. No one pleaded more eloquently for a larger conception of the functions of the national government than

Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

. He called the attention of his hearers to provisions made for coast surveys and lighthouses on the Atlantic seaboard and deplored the neglect of the interior of the country. Of the other presidential candidates,

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

voted in the Senate for the general survey bill; and

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

left no doubt in the public mind that he did not reflect the narrow views of his section on this issue.

William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

felt the constitutional scruples which were everywhere being voiced in the South, and followed the old expedient of advocating a constitutional amendment to sanction national internal improvements.

In President Adams' first message to Congress, he advocated not only the construction of roads and canals but also the establishment of

observatories

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. His ...

and a national university. President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

had recommended many of these in 1806 for Congress to consider for creation of necessary amendments to the Constitution. Adams seemed oblivious to the limitations of the Constitution. In much alarm, Jefferson suggested to Madison the desirability of having Virginia adopt a new set of resolutions, bottomed on those of 1798, and directed against the acts for internal improvements. In March 1826, the

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 161 ...

declared that all the principles of the earlier resolutions applied "with full force against the powers assumed by Congress" in passing acts to protect manufacturers and to further internal improvements. That the administration would meet with opposition in Congress was a foregone conclusion.

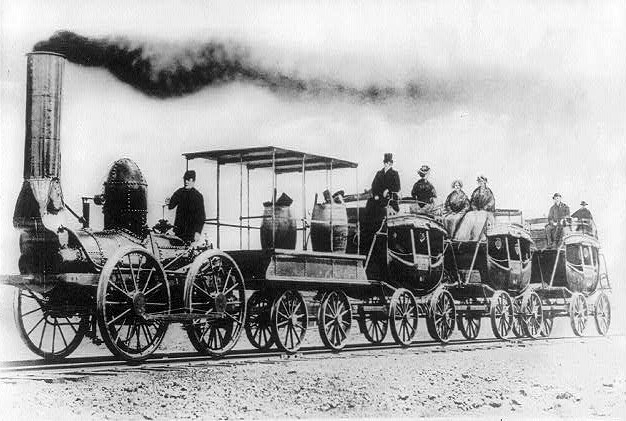

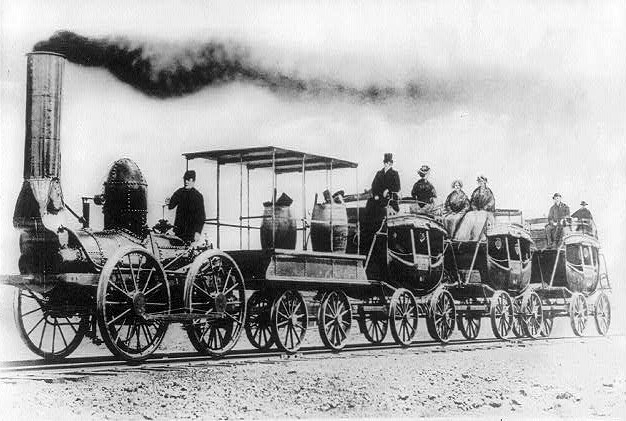

Steamboats

Despite the new efficiencies introduced by the turnpikes and canals, travel along these routes was still time-consuming and expensive. The idea of integrating a steam

boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central h ...

and propulsion system can be first attributed to

John Fitch and

James Rumsey